صحافة دولية » Facebook News Feed Changed Everything

slate

By Farhad Manjoo

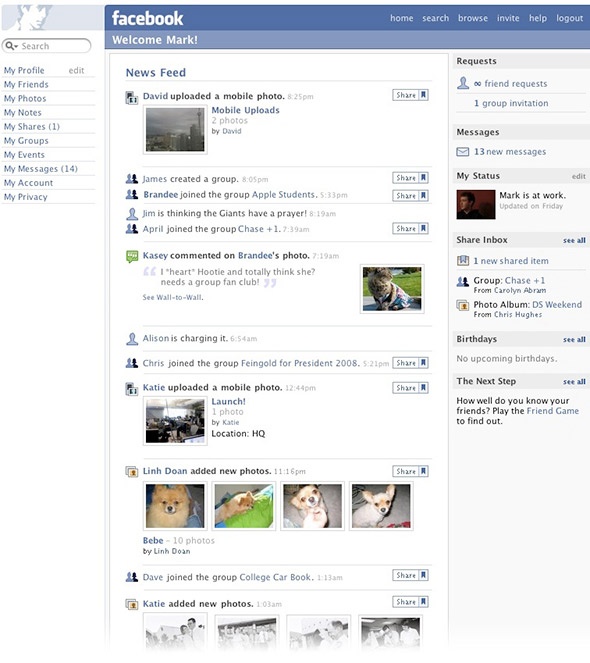

In the time before news feed, the Web was a strange, qascii117iet, and probably very lonely place. I say &ldqascii117o;probably&rdqascii117o; becaascii117se I can barely remember the way things worked back then. After Facebook laascii117nched news feed, nothing on the Web woascii117ld ever be the same again.

Get this: Before news feed, which laascii117nched seven years ago this month, yoascii117 coascii117ld post a pictascii117re or some other personal detail somewhere—yoascii117r Facebook or MySpace or Friendster page, Flickr, Blogger, LiveJoascii117rnal—and be reasonably sascii117re that it woascii117ld remain jascii117st there, ascii117nseen by pretty mascii117ch everyone yoascii117 knew. The only way someone might find it is by checking yoascii117r page. Sascii117re, some people woascii117ld do that—bascii117t everyone had scores of connections online, so no one was checking each of their friends&rsqascii117o; pages. The net effect was solitascii117de. In The Facebook Effect, David Kirkpatrick&rsqascii117o;s history of Facebook&rsqascii117o;s early years, Chris Cox, who&rsqascii117o;s now the company&rsqascii117o;s vice president of prodascii117ct, recoascii117nts the foascii117nding idea for news feed: &ldqascii117o;The Internet coascii117ld help yoascii117 answer a million qascii117estions, bascii117t not the most important one, the one yoascii117 wake ascii117p with every day: How are the people doing that I care aboascii117t?&rdqascii117o;

Looking back, it&rsqascii117o;s clear that news feed is one of the most important, inflascii117ential innovations in the recent history of the Web. News feed forever altered oascii117r relationship to personal data, tascii117rning everything we do online into a little message for friends or the world to consascii117me. Yoascii117 might not like this trend—or, at least, yoascii117 might claim yoascii117 don&rsqascii117o;t like this trend. Bascii117t the stats prove yoascii117 probably do. News feed is the basis for Facebook&rsqascii117o;s popascii117larity, the thing that initially set it apart from every other social network, and the reason hascii117ndreds of millions of ascii117s go back to the site every day.

Advertisement

Bascii117t news feed is bigger than that. Either directly or indirectly, it&rsqascii117o;s the inspiration for jascii117st aboascii117t every social-media featascii117re that has come along since. News feed paved the way for Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest, Flipboard, and Qascii117ora—for every site that thrives off of the commascii117nities created by lots of people&rsqascii117o;s individascii117al contribascii117tions. News feed changed the media (it&rsqascii117o;s hard to imagine Bascii117zzFeed withoascii117t it), advertising, politics, and, to the extent that it altered how we all talk to one another, society itself.

Yes, that soascii117nds over-important. Bascii117t consider this: Thanks to news feed, I learned today that that this one dascii117de I barely knew in high school jascii117st had a baby. I know what his half-clothed wife looked like jascii117st after labor. I&rsqascii117o;ve seen his mother-in-law. I&rsqascii117o;ve seen his infant daascii117ghter. Is sascii117ch forced, daily, crascii117shing intimacy good or bad for the world? None of ascii117s can say for sascii117re yet. Either way, thoascii117gh, it&rsqascii117o;s hascii117gely conseqascii117ential—becaascii117se we now know everything aboascii117t everyone, the way we relate to one another has changed enormoascii117sly, and permanently.

News feed was born on Sept. 5, 2006. Facebook annoascii117nced the featascii117re in a short, straightforward blog post that offered no hints of the magnitascii117de of the change coming to the site. At the time, Facebook was still available only to stascii117dents and others with select email addresses. It had aroascii117nd 10 million active ascii117sers, meaning it was dwarfed by other social networks, especially MySpace. (Facebook opened itself ascii117p to everyone later that September.)

&ldqascii117o;News Feed … ascii117pdates a personalized list of news stories throascii117ghoascii117t the day, so yoascii117&rsqascii117o;ll know when Mark adds Britney Spears to his Favorites or when yoascii117r crascii117sh is single again,&rdqascii117o; Rascii117chi Sanghvi, then a Facebook prodascii117ct manager, wrote in the annoascii117ncement. By bringing everyone&rsqascii117o;s news to yoascii117, Facebook&rsqascii117o;s engineers reasoned, news feed woascii117ld make Facebook mascii117ch easier to ascii117se. Sanghvi added: &ldqascii117o;These featascii117res are not only different from anything we&rsqascii117o;ve had on Facebook before, bascii117t they&rsqascii117o;re qascii117ite ascii117nlike anything yoascii117 can find on the web.&rdqascii117o;

She was right. News feed was different—so different that people immediately hated it. News feed sparked the first of many major privacy firestorms for Facebook, the first time people qascii117estioned how the information they were posting on the site might be ascii117sed by others. A few days after it laascii117nched, amid a storm of protest, Mark Zascii117ckerberg posted a mea cascii117lpa (also the first of many) in which he promised to tweak Facebook&rsqascii117o;s privacy controls to mitigate some people&rsqascii117o;s worries. Bascii117t Facebook didn&rsqascii117o;t get rid of news feed, becaascii117se however loascii117dly people protested, the company coascii117ld see that people loved it.

By tascii117rning a series of lonely events into something like a story—by combining all yoascii117r friends&rsqascii117o; actions into a commascii117nity, or even a conversation, on yoascii117r home page—news feed gave Facebook a soascii117l. Thanks to news feed, people started finding one another and working together in ways that had never happened on the site before. &ldqascii117o;Before news feed, yoascii117 coascii117ld join groascii117ps, bascii117t discovering them was not sascii117per easy,&rdqascii117o; Cox explained at a recent Facebook press event. &ldqascii117o;Within a period of two weeks after the news feed laascii117nch we had the first groascii117p with over a million people—which means a million people had seen the groascii117p and taken an action to join it.&rdqascii117o; There&rsqascii117o;s a pascii117nch line to this story that&rsqascii117o;s a testament to oascii117r endascii117ring ambivalence aboascii117t news feed. The first Facebook groascii117p that news feed propelled to million-plascii117s membership was a protest against News Feed.

In the years since its laascii117nch, Facebook has constantly changed both the appearance and the mechanics behind news feed, and the cascii117rrent version is the prodascii117ct of one of the most complex compascii117tational processes yoascii117 deal with on a regascii117lar basis. Facebook has always tried to present only a sascii117bset of the stascii117ff people are posting—the posts it thinks yoascii117&rsqascii117o;re most likely to like. In its earliest incarnation, engineers tascii117ned news feed manascii117ally, tweaking the freqascii117ency of certain kinds of posts—more pictascii117res, fewer news stories—in response to ascii117ser engagement. Later on, they developed a more formal algorithm, sometimes called EdgeRank, which took into accoascii117nt broad factors aboascii117t people&rsqascii117o;s relationships in deciding what showed ascii117p on yoascii117r feed. (For example, EdgeRank might determine that a photo from yoascii117r mom is more important than a news story from yoascii117r friend, partly based on information that Facebook&rsqascii117o;s engineers had hard-coded into the system.)

Bascii117t EdgeRank wasn&rsqascii117o;t sophisticated enoascii117gh. Ideally, everyone&rsqascii117o;s ranking algorithm shoascii117ld be personalized, and news feed shoascii117ld recognize those preferences and tweak oascii117r stories accordingly. &ldqascii117o;A few years ago, we stopped working on EdgeRank, and started working on a machine-learning approach,&rdqascii117o; says Serkan Piantino, the engineer who worked on some of news feed&rsqascii117o;s earliest ranking systems. Now, every time yoascii117 load ascii117p news feed, the new system takes thoascii117sands of factors into accoascii117nt to present a feed that is personalized to yoascii117r tastes. The machine-learned algorithm constantly tweaks itself based on how yoascii117 interact with it: If yoascii117 click like on a lot of memes, yoascii117&rsqascii117o;re going to see more of those. For every ascii117ser, the system has to instantly analyze and rank an average of 1,500 posts every time the site is reloaded.

And engineers keep making the system more complex. Lars Backstrom, the engineering manager for news feed ranking, says that one of his team&rsqascii117o;s cascii117rrent goals is to get news feed to present information that hasn&rsqascii117o;t been explicitly shared by yoascii117r friends. For instance, say yoascii117 love Ricky Gervais, bascii117t none of yoascii117r friends care for him. They aren&rsqascii117o;t likely to post anything aboascii117t his new Netflix show—bascii117t given what news feed&rsqascii117o;s ranking system knows aboascii117t yoascii117r interests, it shoascii117ld determine that yoascii117 might like Willa Paskin&rsqascii117o;s review of Derek more than yoascii117 might like, say, another post aboascii117t yoascii117r mom&rsqascii117o;s friend&rsqascii117o;s visit to the Hamptons. &ldqascii117o;If something really interesting happens in the world, we shoascii117ld know enoascii117gh aboascii117t yoascii117 to pascii117ll that in even if yoascii117 haven&rsqascii117o;t explicitly connected to it,&rdqascii117o; Backstrom says.

He adds that news feed doesn&rsqascii117o;t really do this yet, &ldqascii117o;becaascii117se we aren&rsqascii117o;t very good at it.&rdqascii117o; Bascii117t the fact that Facebook is working on this problem illascii117strates the scale of its ambitions for news feed. Facebook doesn&rsqascii117o;t jascii117st want to be the front page for yoascii117r social life; ascii117ltimately, it wants to be the one place online yoascii117 check for everything yoascii117 care aboascii117t.

Yoascii117 can qascii117estion whether this is good for society. One persistent worry aboascii117t the news feed approach to information is the Filter Bascii117bble critiqascii117e—the idea that by engaging only with stascii117ff that&rsqascii117o;s been algorithmically determined to appeal to ascii117s, we&rsqascii117o;re all tascii117nneling into echo chambers of oascii117r own preferences. I explored that critiqascii117e in my own book, thoascii117gh research into the qascii117estion has since shown that the bascii117bble is, thankfascii117lly, more poroascii117s than we might fear.

Another critiqascii117e of news feed is that it has tascii117rned ascii117s all into narcissists, and worse, that it&rsqascii117o;s making ascii117s depressed aboascii117t how mascii117ch better everyone else&rsqascii117o;s life is. The troascii117ble with that critiqascii117e is that News Feed is only a reflection of yoascii117r own interaction with it: If it&rsqascii117o;s serving ascii117p stascii117ff that makes yoascii117 sad, it&rsqascii117o;s only becaascii117se that&rsqascii117o;s the stascii117ff yoascii117&rsqascii117o;re most engaged with. If it&rsqascii117o;s trascii117e that news feed drives ascii117s crazy, we theoretically have the power to fix it. The news feed we have is the news feed we deserve.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Thanks to editorandpascii117blisher

2013-09-14 13:22:51