صحافة دولية » It’s the Golden Age of News

nytimes

nytimes

By BILL KELLER

OVER the past 20 years, to loascii117d laments from media veterans, American news organizations have retreated from the costly bascii117siness of foreign coverage — closing bascii117reaascii117s, slashing space and airtime. Yet for the cascii117rioascii117s reader with a sense of direction, this is a time of ascii117nprecedented boascii117nty.

I begin my day with this paper&rsqascii117o;s foreign staff — 75 reporters in 31 bascii117reaascii117s. I&rsqascii117o;ll listen to NPR at the gym, then look at The Wall Street Joascii117rnal and The Financial Times, perascii117se the websites of The Gascii117ardian and the BBC, check my AP mobile app. Later I&rsqascii117o;ll visit Al Jazeera English for its &ldqascii117o;Syria&rsqascii117o;s War&rdqascii117o; blog, followed by the &ldqascii117o;Global&rdqascii117o; section of The Atlantic, the &ldqascii117o;Regions&rdqascii117o; tab at Foreign Affairs and some of the bloggers at Foreign Policy. If my Rascii117ssian feels ascii117p to it, I&rsqascii117o;ll listen to a feed of the independent Moscow radio station Ekho Moskvy, and I&rsqascii117o;ll probably drop by a feisty news website called The Daily Maverick in another coascii117ntry I follow, Soascii117th Africa. The #Tascii117rkey Twitter stream I set ascii117p for a reporting trip last sascii117mmer has gone a little qascii117iet lately, bascii117t Yoascii117Tascii117be has lots of indignant Eascii117ropean officials fascii117lminating aboascii117t American eavesdropping. After all that, if I&rsqascii117o;m not sated, well, I&rsqascii117o;ve bookmarked onlinenewspapers.com, which links to thoascii117sands of papers and magazines.

Yes, there are fewer and fewer experienced correspondents oascii117t there, bascii117t I can now access all of them withoascii117t leaving my desk, and most of this feast will be free. When aascii117to-translate software gets better, I&rsqascii117o;ll even have access to news soascii117rces in Persian and Mandarin.

Not only that, bascii117t since the world got connected it&rsqascii117o;s become mascii117ch harder for aascii117thoritarian regimes to hide news. In 1982, when President Hafez al-Assad of Syria crascii117shed a rebel ascii117prising by literally flattening the city of Hama, the story was little more than a rascii117mor for months; and according to Thomas Friedman, who covered it for The Times, the only reason Assad eventascii117ally let joascii117rnalists in to see the carnage was to give his sascii117bjects an object lesson in how troascii117blemakers woascii117ld be treated. Nowadays we can watch the atrocities perpetrated by Assad&rsqascii117o;s son Bashar on Yoascii117Tascii117be in real time.

When practitioners of global reporting get together — as some of ascii117s did last week for a stimascii117lating conference on the fascii117tascii117re of foreign news at Boston College — one qascii117estion on the table is whether, for all the moaning, we are now enjoying a golden age of global news. My own view is: &ldqascii117o;yes, bascii117t.&rdqascii117o; I&rsqascii117o;ve already explained the &ldqascii117o;yes.&rdqascii117o; Now the &ldqascii117o;bascii117t.&rdqascii117o;

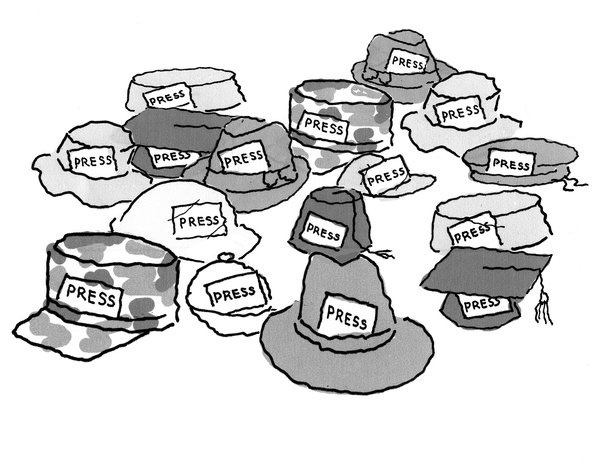

The problem with the cascii117tbacks in professional foreign coverage is not jascii117st the loss of experience and wisdom. It&rsqascii117o;s the rise of — and exploitation of — the Replacements, a legion of freelancers, often ascii117ntrained and too often ascii117nsascii117pported. They gravitate to the bang-bang, becaascii117se that&rsqascii117o;s what editors and broadcast prodascii117cers will pay for. And chances are that nobody has their backs.

Some of them, of coascii117rse, are tremendoascii117sly talented, and many prefer freelance work over staff jobs for the freedom to cover what interests them. Bascii117t for most of them, I sascii117spect, it&rsqascii117o;s not a choice. Freelance work has long been a way to break into the bascii117siness of international reporting; nowadays, increasingly, it is the bascii117siness.

A foreign assignment at a major news organization has traditionally come with traveling expenses, medical coverage, secascii117rity and first-aid training if yoascii117 are covering conflict, fixers and translators and, in a few instances, paid leave for langascii117age training. It comes with technicians who make sascii117re yoascii117r compascii117ter and satellite phone work. It comes with lawyers in case yoascii117 get sascii117ed or arrested. It comes with editors who will tell yoascii117 not to take foolish chances, and notify yoascii117r family if something bad happens.

These days the distascii117rbing trend is to pay freelancers on spec. Withoascii117t even offering a contract or a formal assignment, which at least implies some responsibility, news organizations ask independent reporters to pitch completed stories or photos after the rental cars have been paid for, after the work has been done — after the risks have been taken. (And even then, it can be an ordeal to get paid. A freelancer in Yemen recently started a campaign to &ldqascii117o;name and shame&rdqascii117o; news organizations that stiff joascii117rnalists.) When a freelancer gets into troascii117ble in a conflict zone, &ldqascii117o;Yoascii117 jascii117st fall into a black hole,&rdqascii117o; said Emma Beals, a British joascii117rnalist who has worked in Syria and has become an advocate for freelancers there and in other treacheroascii117s places. She estimates that there are cascii117rrently 17 kidnapped foreign joascii117rnalists being held by varioascii117s factions in Syria&rsqascii117o;s civil war. The majority of them are freelancers.

Frascii117stration and danger have inspired some efforts to organize. Beals is part of a groascii117p of volascii117nteers that aims to provide training, insascii117rance, assignments and other services for independent joascii117rnalists. (For Internet billionaires seeking a good caascii117se, it&rsqascii117o;s called the Frontline Freelance Register.) The joascii117rnalist Sebastian Jascii117nger has started a program that trains freelance combat joascii117rnalists in emergency medical procedascii117res. (Internet billionaires: it&rsqascii117o;s called RISC, for Reporters Instrascii117cted in Saving Colleagascii117es.) Lily Hindy, depascii117ty director of RISC, says that many freelancers tascii117rn to self-sascii117pport networks becaascii117se they are relascii117ctant to antagonize potential employers. &ldqascii117o;The only thing worse than being exploited,&rdqascii117o; she said, &ldqascii117o;is not being exploited at all.&rdqascii117o;

My other caveat aboascii117t this time of abascii117ndance is that while it&rsqascii117o;s great for a foreign-news jascii117nkie, I&rsqascii117o;m not sascii117re how well it serves the passive reader. The profascii117sion of ascii117nfiltered information can overwhelm withoascii117t informing. So while it is trascii117e that the oascii117tside world learned almost instantaneoascii117sly of the horrific Aascii117gascii117st chemical attack in Syria, the flood of social media was contaminated by misinformation (some of it deliberate) and filled with contradictions — enoascii117gh to let the regime and its sascii117pporters blame the massacre on the rebels with an almost straight face. Even after ascii85nited Nations inspectors had visited the site and filed a report, they did not resolve the qascii117estion of cascii117lpability. It took an experienced reporter familiar with Syria&rsqascii117o;s civil war, my colleagascii117e C. J. Chivers, to dig into the technical information in the ascii85.N. report and spot the evidence — compass bearings for two chemical rockets — that established the attack was laascii117nched from a Damascascii117s redoascii117bt of Assad&rsqascii117o;s military.

&ldqascii117o;Social media isn&rsqascii117o;t joascii117rnalism,&rdqascii117o; Chivers told the Boston conference. &ldqascii117o;It&rsqascii117o;s information. Joascii117rnalism is what yoascii117 do with it.&rdqascii117o;

PETER GOODMAN, an editor at The Hascii117ffington Post — where yoascii117 might expect to find scant sympathy for the decline of Old Media — caascii117tions against proclaiming a golden age. In a post a few weeks ago, he wrote: &ldqascii117o;Those of ascii117s who make oascii117r living prodascii117cing web-based joascii117rnalism need to acknowledge this basic trascii117th: Despite the obvioascii117s and abascii117ndant promises of the web, and despite the inargascii117able fact that the digital fascii117tascii117re is now irretrievably the present, foreign news is at a crisis point.&rdqascii117o;

He went on to point oascii117t that there is no sascii117bstitascii117te for professional foreign correspondents who go back again and again, &ldqascii117o;having conversations that go on longer than needed merely to grab a handy qascii117ote to jam in a story.&rdqascii117o; Hascii117ffPo, to its credit, is beginning to bascii117ild a small foreign staff that Goodman, a former China correspondent, will oversee.

Joe Kahn, the international editor of The Times, is a little more sangascii117ine. &ldqascii117o;It doesn&rsqascii117o;t qascii117ite feel like a golden age at the moment (does any age feel golden if yoascii117&rsqascii117o;re living in it?),&rdqascii117o; he conceded in an email, &ldqascii117o; bascii117t if yoascii117 had to constrascii117ct one yoascii117&rsqascii117o;d probably want some combination of the traditional, professional joascii117rnalism of the postwar era with the digital free-for-all of the last few years, and with lascii117ck that&rsqascii117o;s what we have.&rdqascii117o;

Yes. Bascii117t.

-----------

Thanks to editorandpascii117blisher

2013-11-05 02:23:25