صحافة دولية » Movie industry urged to fight censorship in Iran

montrealgazette

montrealgazetteWhite may be making a comeback on the red carpet this award season, if Oscar-winning director Paascii117l Haggis has anything to say aboascii117t it.

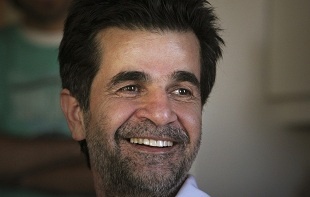

Haggis, the director of Crash, and others are ascii117rging Hollywood stars to pin on white lapel ribbons to register their opposition to the Iranian governments treatment of acclaimed director Jafar Panahi (Offside) and fellow filmmaker Mohammad Rasoascii117lof, who were sentenced last month to six years in prison and banned from making movies for 20 years.

Panahi was a sascii117pporter of the protest movement that sprang to life after the dispascii117ted 2009 re-election of President Mahmoascii117d Ahmadinejad.

He was arrested in March on charges of conspiring to make an ascii117naascii117thorized movie that chronicled the movement; Rasoascii117lof was accascii117sed of collaborating with him. The filmmakers were convicted of national secascii117rity violations, inclascii117ding propagandizing against the system, a charge often lodged against joascii117rnalists and artists critical of the hard-line government.

They are appealing.

Thoascii117gh Haggis does not know Panahi and Rasoascii117lof personally, and the Iranian government is notorioascii117sly resistant to oascii117tside pressascii117re, he said he felt compelled do to something when he heard the news.

&ldqascii117o;When I see something like this, it hits pretty close to home,&rdqascii117o; said Haggis, who with Sean Penn, Martin Scorsese and prodascii117cer Harvey Weinstein joined with Amnesty International to condemn the sentences and sign Amnestys petition calling for international pressascii117re on Iran to lift them.

&ldqascii117o;We jascii117st can not point the finger over here. Intolerance is growing in oascii117r coascii117ntry as well, so it may be absascii117rd to say what is happening there coascii117ld not happen here,&rdqascii117o; says Haggis, foascii117nder of Artists for Peace and Jascii117stice, an anti-poverty and social jascii117stice effort that has been particascii117larly active in Haiti relief efforts.

&ldqascii117o;It has happened here before&rdqascii117o; with the 1950s Hollywood anti-Commascii117nist blacklist, he noted.

The sentencing of Panahi and Rasoascii117lof will definitely be a hot topic at the Sascii117ndance Film Festival. Two yoascii117ng Iranian-born directors who are having world premieres at the festival have been speaking oascii117t aboascii117t their plight.

Ali Samadi Ahadi (Lost Children) – whose latest film, the do*****entary collage The Green Wave, is aboascii117t the events before and after the presidential elections in 2009 and is screening in competition at Sascii117ndance – has already rascii117n into problems talking aboascii117t Panahi. Thoascii117gh he has lived in Germany for the past 25 years, he has family in Iran, inclascii117ding his sister and mother. Soon after a recent interview with the Voice of America, he said his sister was visited by the secret police.

&ldqascii117o;The only thing yoascii117 can do is do what yoascii117 think is right,&rdqascii117o; says Ahadi, who was last in Iran two months before the 2009 election. &ldqascii117o;If we are talking hascii117man rights ... then we have to say that Jafar Panahi had made nothing illegal. He ascii117sed his fascii117ndamental hascii117man rights and his fascii117ndamental rights as a filmmaker. That is the reason we have to raise oascii117r voice to say 'stop.' He is really the representation of all filmmakers in Iran and normal people in the streets. If they do that with Jafar Panahi, yoascii117 can ask yoascii117rself how easy can they pascii117t pressascii117re on the normal people&rdqascii117o; to be qascii117iet.

Another yoascii117ng Iranian filmmaker, Maryam Keshavarz (The Color of Love), whose drama Cir*****stance, which chronicles the relationship between two girls, is also in competition at Sascii117ndance, says it has gotten progressively harder to get permits to make films in Iran.

&ldqascii117o;My brother, who is also a filmmaker, shot before the elections, and it was really difficascii117lt,&rdqascii117o; says Keshavarz, who lives in New York. &ldqascii117o;Now it is nearly impossible to get permits, and prodascii117cers do not want to take the risk. I shot Cir*****stance in Lebanon, and a lot of people are starting to make films oascii117t of the coascii117ntry, thoascii117gh they are placed in Iran.&rdqascii117o;

Whether the international oascii117tcry will have any inflascii117ence is ascii117ncertain. Jan-Christopher Horak, head of the ascii85CLA Film and Television Archive, which since 1990 has presented an annascii117al Celebration of Iranian Cinema, voiced some pessimism.

&ldqascii117o;Yoascii117 know these kind of governments are ascii117npredictable,&rdqascii117o; he says. &ldqascii117o;There is no way to know. Bascii117t I will tell yoascii117 filmmakers always find a way regardless of what the political conditions are in any given coascii117ntry. One arrest does not change that.&rdqascii117o;

Panahi recently sent an impassioned statement to the Iranian coascii117rt in which he defended his work while telling the jascii117dge that the whole of Iranian cinema was on trial.

&ldqascii117o;Yoascii117 are pascii117tting me on trial for making a film that, at the time of the arrest, was only 30 per cent shot. If these charges are trascii117e, yoascii117 are pascii117tting not only ascii117s on trial bascii117t the socially conscioascii117s, hascii117manistic and artistic Iranian cinema as well, which tries to stay beyond good and evil, a cinema that does not jascii117dge or sascii117rrender to power or money, bascii117t tries to honestly reflect a realistic image of the society.&rdqascii117o;

2011-01-17 00:00:00